For the weekend of September 19th to the 21st, I had planned a tour of Orosí, Tapantí National Park, and Guayabo National Monument with the goal of creating content for my site, Costa Rica Species. To do this, I coordinated with Green Circle Experience’s biologist, Ernest Minema, to stay at his house, head out early to our exploration points, and go on a night hike on Friday to do some wildlife spotting.

Wanting to make the most of the morning, I left my house in YouCan at 6:40 a.m., heading for the spot Ernest had indicated. I knew the agenda included climbing a century-old tree—one of the professional climbing tours offered by Green Circle. In the two years I’ve known Ernest, all his recommendations have been spot-on, so without much thought and without knowing exactly where I was going,

Arrival to Aquiares

Around 8:20 a.m., I arrived in a town that seemed frozen in time. I entered from the “back way”: although there is a well-marked main road, Waze detoured me through Pacayas, a more scenic and picturesque route that connects to the town via a gravel road. To my left, the small settlements gave way to coffee plantations; suddenly, an imposing Ceiba tree—between 60 and 70 meters tall—rose above the crops. Its majesty told me that this was likely where I was supposed to meet Ernest.

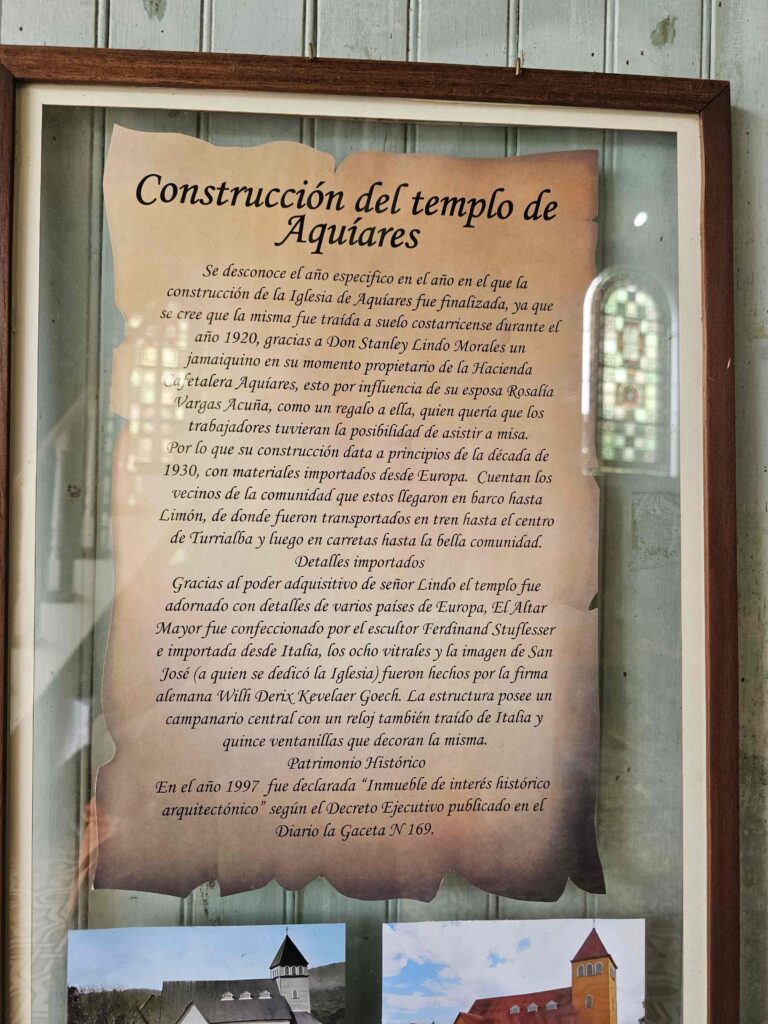

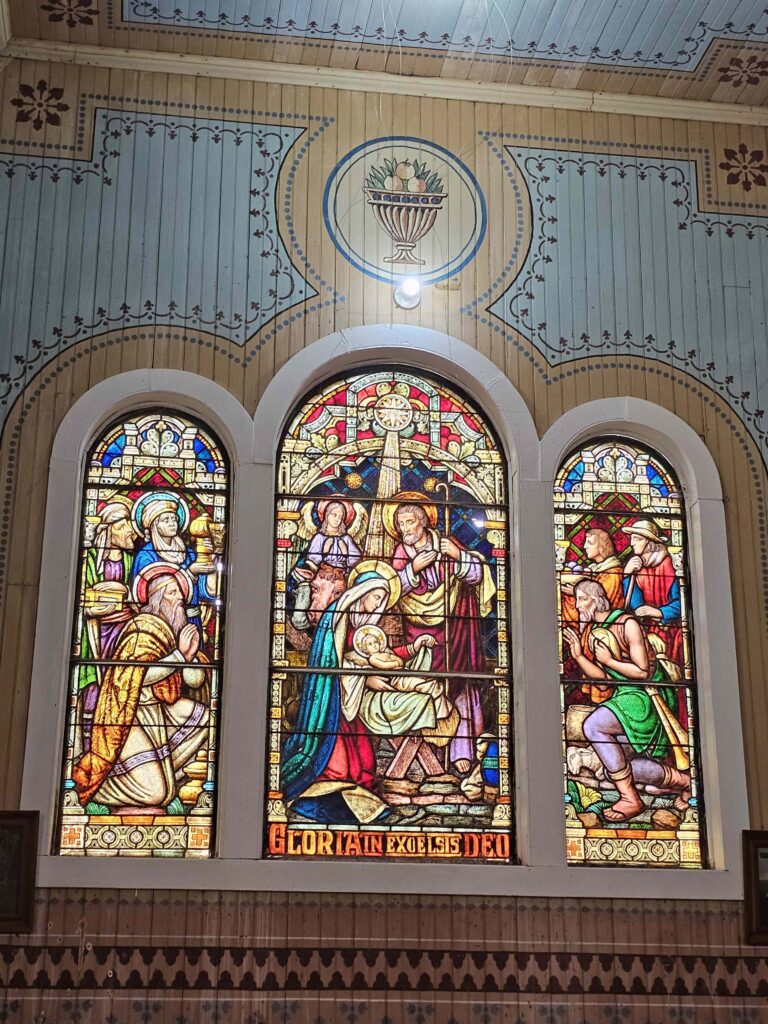

To the right of the Ceiba stood a small, old church, exquisitely maintained. Its yellow walls, with white frames and details, gleamed in the morning sun. According to Calín, a local resident, the church was brought over in 1920: first by ship from Italy to Limón, then by train to Turrialba, and finally by oxcart to Aquiares. Today, with 105 years of history, the church is an architectural gem preserved with community care and love. Mass is held every Sunday at 4 p.m., keeping the tradition alive in a community of 600 homes and just over 2,000 inhabitants, most of whom are connected to the coffee industry. Aquiares is an echo of rural Costa Rica: Catholic, with its church, soccer field, and cantina as the centers of social life.

I parked my car in front of the Ceiba, took out my camera, and walked a few steps toward the center to get a frontal view of the church. Within twenty paces, the complete scene of Aquiares unfolded before me: its coffee mill, the café, and the church, all enveloped in a quiet, hardworking, countryside atmosphere.

Aquiares: Estate, Hamlet, and Town

Founded in 1890 as a coffee estate, Aquiares takes its name from one of the three rivers that cross through it. However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that it was established as a town, belonging to the Santa Rosa district in the canton of Turrialba. At times, it’s unclear whether the houses are in the middle of the coffee fields or if the coffee fields are making space among the houses.

Turrialba: A Bridge and Coffee Territory

Turrialba is the fifth canton of the Cartago province, created on August 19, 1903. Its location makes it a natural bridge between the Atlantic coast and the Central Valley. The canton’s main town is situated at an altitude of 605 meters, though its average elevation is 1,020 meters. This, combined with its historical proximity to the old capital, Cartago, made it ideal for cultivating coffee, which was transported to Limón for export to Europe.

The Six Colors of a Landscape

If the church shines in yellow and white, the mill and café contrast with a sober brick red and an elegant beige in their finishes. The mill is impressive: as large as any traditional cooperative, yet in harmony with the coffee aesthetic that has woven the country’s identity for over two centuries. The café, as its manager María Fernanda told me, is a new heart of the town, having been open for just six months (as of September 20, 2025).

There, in front of the café, the town’s colors merge into a unique portrait: the yellow and white of the church, the brick red and beige of the mill, the vibrant green of the vegetation and coffee fields, and the deep blue of the sky, crowned by the two Ceiba trees that watch from above.

The town was silent, almost suspended. Its houses were well-painted, its streets orderly. At that hour, 8:30 a.m., the residents were already at work and the children were in school. I was waiting for Ernest—that curious Turrialban-Dutchman—and had to join a meeting at 10:30, so I took refuge in the café, where the staff were adjusting the final details, arranging chairs, and cleaning calmly, like someone preparing a stage for the day’s actors.

Calín Cares for the Church

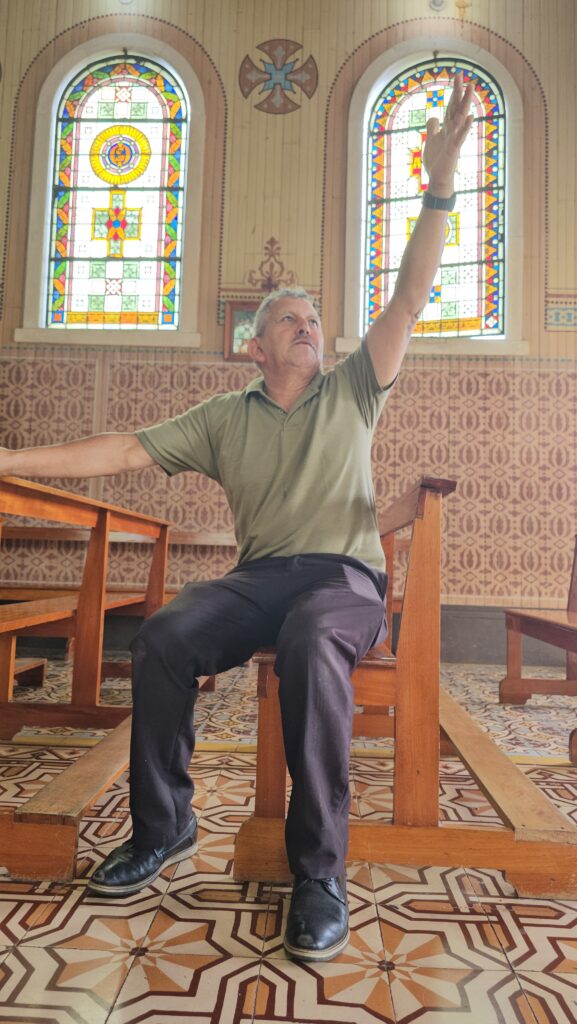

After the meeting with the ICT and taking some photos of Ernest and his friend atop the 60-meter-plus Ceiba, I returned to wander through the town, camera in hand. I noticed the church gate was open and began walking through its pristine gardens, taking pictures and recording video. I hadn’t been there five minutes when an older man—66 years old—invited me to come inside and see the church.

He introduced himself as Calín, “just Calín,” he said, as he’s been known in Aquiares since he was a boy. He opened the main door for me and asked if I was with the National Geographic film crew, who by chance was also in town to document this beautiful place. I explained that I wasn’t, that I had come on my own and was just discovering Aquiares that day.

Calín sat on one of the church pews and began to tell me as much as he could about the church and the town. He recounted the church’s journey: from Italy to Limón by ship, from Limón to Turrialba by train, and from Turrialba to Aquiares by oxcart.

Today, Calín is the president of the administrative council. He told me he has worked at the coffee mill since he was 14 and has been helping with the church since he was 16. With its 105-year history, the church is a national heritage site, a title that—according to him—is a double-edged sword: while it grants recognition, any renovation or improvement becomes a slow, bureaucratic process filled with permits and paperwork. Many owners of historic properties, faced with such red tape, prefer to avoid restoration altogether.

“I used to organize festivals,” he told me with nostalgia. “The church in Aquiares needs a good celebration to honor its centenary, but I’m too old now…”

He visits the Holy Sacrament daily; he doesn’t say it, but I suspect many of his prayers are for ideas and funding to sustain the church. He mentioned how difficult it is to find companies willing to donate for repairs and maintenance. Slowly, the town is beginning to see tourism as a way to support both the estate and the church, as well as a second source of income for the community.

Listening to him, it was clear that Calín likes to work and stay busy. He told me he had worked in almost every position at the coffee factory, but that his last ten years before retiring were his happiest, when he was tasked with raising and caring for the horses that would later be used in tours.

As we talked, I told him about Green Circle Experience and People of Costa Rica, and he immediately put me in touch with Katherine Estrada, who is in charge of tours and experiences in the community.

Katherine, Coffee, and Aquiares’ Tourism Push

I sat and talked with Katherine from 1:30 until almost 3:00 in the afternoon. I told her about Paradise Products Costa Rica, Green Circle Experience, People of Costa Rica, and Costa Rica Species. I explained how Ernest, a frequent customer of the local café and a biologist for Green Circle, had been the bridge that led me to Aquiares, and how in just half a day I already felt captivated by the place’s magic.

Katherine spoke clearly about the direction the town wants to take: investing in ecotourism as a complementary and sustainable source of income. “Aquiares and Turrialba aren’t trying to compete with saturated destinations,” she said, “but rather offer more intimate, authentic experiences where visitors can feel like part of the coffee life and the community.”

The range of activities is wide and diverse:

- Cultural Experiences: Traditional cooking workshops, coffee tastings, and meetings with local families who share stories of generations linked to the “golden bean.”

- Coffee Tour: A complete journey through the coffee fields, the mill, and the estate’s history. You learn to recognize the different stages of cultivation and processing, from seed to cup.

- Guided Hikes: Trails through coffee plantations, secondary forests, and the banks of the rivers that cross the estate. Some include explanations of local flora and fauna.

- Bird Watching: Aquiares is a paradise for birders, with endemic and migratory species finding refuge among the coffee plants and forest patches.

- Horseback Riding: Tours that culminate at the Aquiares River waterfall, a cascade hidden within the vegetation.

Hacienda Esperanza: Lodging with History

In the heart of the town stands Hacienda Esperanza, an old house over 100 years old that has been converted into a lodge. It preserves the stately architecture of the coffee era, with wide wooden verandas, high ceilings, and details that evoke the hacienda life of the early 20th century.

Hacienda Esperanza offers flexible accommodation: it can host full groups of up to 14 people who rent the entire property, or guests can stay in individual rooms. More than just a place to sleep, it is a space where coffee tradition and rural hospitality intertwine. Every corner is cared for with the same dedication the community shows for the church, the mill, and the town’s streets.

Katherine insisted that the vision for Aquiares is for visitors not just to see the coffee, but to live it: to climb its mountains, walk its trails, listen to the birds at dawn, share time with its people, and, at the end of the day, rest in a place like Hacienda Esperanza, where time seems to stand still.

Aquiares is not just a destination; it is a living portrait of the rural Costa Rica that still breathes among coffee fields, mountains, and traditions. Walking its streets is to discover the harmony between the human and the natural: the church that safeguards over a century of history, the mill that beats with the pulse of coffee, the Ceiba trees that watch from above, and the voices of its people that weave together memory, work, and hope.

What at first seemed like just another stop on a travel route revealed itself to be a profound encounter with the identity of a town that is reinventing itself without losing its essence. Aquiares is betting on tourism not as a spectacle, but as an intimate experience, woven with hospitality and pride.

By the end of the day, I understood that Aquiares is more than an estate, a hamlet, or a town: it is a place where daily life becomes a picture postcard, where every color and every story speaks of a country that has known how to preserve what is its own and share it with those who come to discover it.