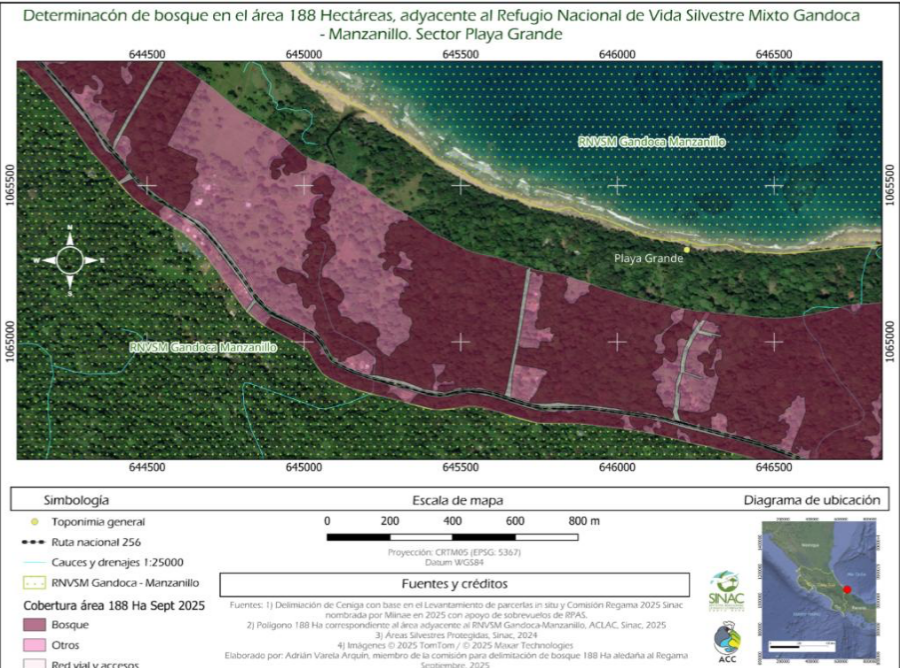

Core Problem: The Unprotected Forest

The core of the current conflict in the Gandoca-Manzanillo National Wildlife Refuge is the identification of 107.9 hectares of primary and secondary forest that have been left in a state of legal vulnerability. The direct cause of this lack of protection is the approval of Law No. 9223 in 2014, which, in an attempt to solve a long-standing land tenure problem, generated an uncontrolled side effect. The main consequence is the creation of a legal vacuum that weakens the State’s ability to prevent deforestation and regulate development on these lands, which are now in the process of being titled as private property.

Historical Context (The Pre-2014 Situation)

To understand the current legislation, it’s essential to analyze the origin of the conflict. The Gandoca-Manzanillo National Wildlife Refuge was established by the state in 1985, protecting one of the country’s most biodiverse areas. However, this protected area was drawn over territories that were already occupied by local settlers, some families having lived there for generations. This overlap of a protected area onto inhabited lands generated a situation of profound legal uncertainty and social tension for nearly three decades.

Despite their deep roots, the inhabitants lacked property titles, which legally prevented them from selling, inheriting, or using their land as collateral for loans. They lived under the constant threat of eviction and faced enormous hurdles in obtaining building permits or basic services, limiting their development. This prolonged uncertainty fueled a strong community movement that lobbied politically for a definitive solution to recognize their possession rights.

Law No. 9223 of 2014: The Controversial Solution

As a direct response to the social pressure and the inhabitants’ long-standing legal uncertainty, the Legislative Assembly passed Law No. 9223, the “Law for the Recognition of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the South Caribbean,” in 2014. The law’s stated purpose was noble: to regularize the situation for legitimate occupants and finally grant them the property rights they had demanded for decades.

To achieve this, the legal mechanism consisted of removing the protected status from the parcels of land that were occupied before the 1996 Forestry Law, thereby allowing them to be titled to private individuals. In practice, this meant creating enclaves of private property within a protected wildlife area. However, from the moment it was debated, the law was intensely controversial. Environmental organizations, biologists, and the Attorney General’s Office itself warned of the inherent risks, arguing that it would inevitably fragment the ecosystem and open a dangerous door to real estate speculation and uncontrolled development by weakening MINAE’s oversight of these critical lands.

Impact and Consequences (Post-2014)

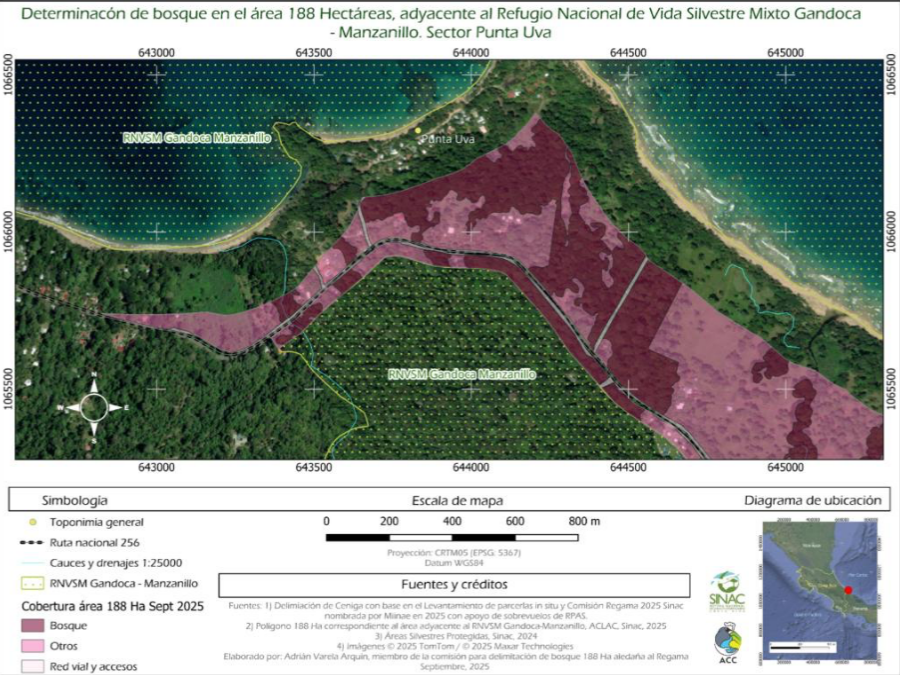

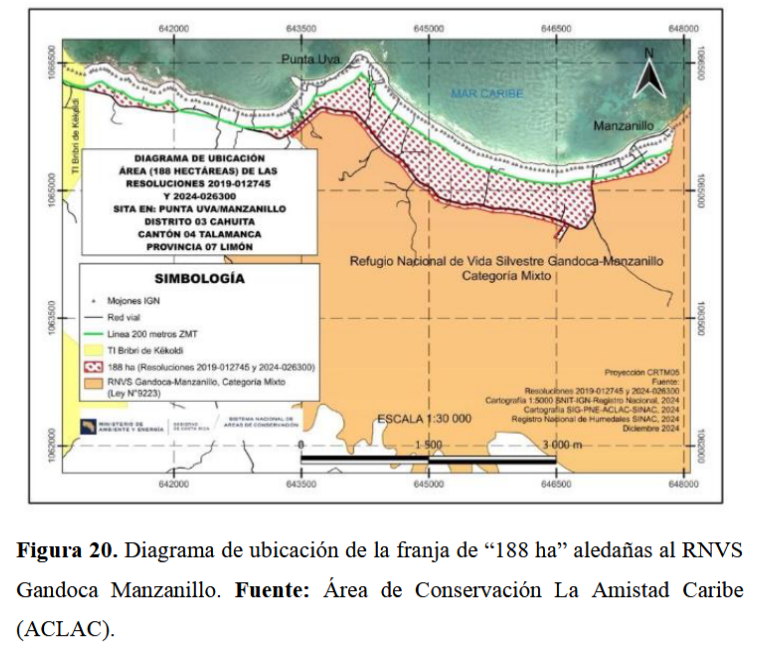

A decade after the law came into effect, its consequences are tangible and have been quantified. A recent technical report from the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC), released in 2025, is the centerpiece of the current situation, as it precisely identifies the 107.9 hectares of primary and secondary forest located within the now-privatized parcels. This finding confirms the fears expressed in 2014.

The most severe impact is the legal vacuum created: as these lands become private property, MINAE has lost its strongest legal tools to sanction or prevent logging, as they no longer operate under the strict regime of a state-protected area. The ecological impact has been documented by conservation organizations, which report a notorious increase in deforestation to make way for construction and a surge in real estate speculation. This situation directly threatens the integrity of the refuge’s ecosystems, endangering vital biological corridors, the habitat of endangered species like the great green macaw, and the health of the wetlands and coral reefs that depend on the coastal forest’s balance.

Key Actors and Their Current Positions (October 2025)

The Gandoca-Manzanillo conflict involves several actors with often conflicting interests and perspectives. As of today, their positions are as follows:

- MINAE / SINAC (Executive Branch): Armed with the technical evidence from the report identifying the 107.9 hectares, this actor officially acknowledges the environmental damage. However, its capacity for direct action is severely limited by Law 9223. Its stance is to seek solutions through alternative means such as negotiation or recommending legal action, although it cannot reverse the law on its own.

- Settlers and Landowners: This is not a homogeneous group. On one hand, there are inhabitants and local entrepreneurs who advocate for sustainable development and conservation, viewing the refuge’s value as their main asset. On the other hand, there are landowners who, protected by their new rights, have proceeded to sell their land to real estate developers or start construction for commercial purposes, maximizing the economic value of their parcels.

- Conservation Organizations: Led by groups like the Costa Rican Conservation Federation (FECON), they maintain a position of firm opposition to the law, labeling it an “ecocide.” Their main battlefront is legal, having filed and actively pursuing constitutional challenges to have the law repealed in its entirety.

- Constitutional Court (Sala IV – Judicial Branch): This is the decisive actor at this moment. The high court is responsible for ruling on the constitutional challenges that have been filed. Its decision will determine whether Law 9223 is upheld, modified, or annulled, making it the final arbiter of the legal future of the refuge and the 107.9 hectares of disputed forest.

Scenarios and the Immediate Future (October 2025)

As of today, the future of the forest within Gandoca-Manzanillo depends on the convergence of several complex courses of action with no guarantee of success. The outlook is uncertain, and four possible paths to address the problem are emerging:

- The Legal Path: This is the most decisive route. All parties are awaiting the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the challenges filed against Law 9223. A decision declaring the law unconstitutional could nullify the titling processes and return full control to MINAE, although it would also reignite the social conflict over land tenure.

- The Negotiated Path: MINAE could attempt a mitigation strategy by negotiating directly with the owners of the 107.9 hectares to enroll their land in the Payment for Environmental Services (PES) program. This would offer them an economic incentive to conserve the forest, but its success depends on the owners’ willingness and the availability of funds.

- The Economic Path: This involves the expropriation of the lands by the State to reintegrate them into the national natural heritage. However, this is the most expensive and logistically complex option, as it would require a multi-million dollar investment to pay the fair market value for lands that have appreciated enormously.

- The Political Path: This implies advancing a legislative reform of Law 9223 to add stricter environmental clauses and controls that would compel landowners to preserve the forest cover. This path is politically difficult and would require a broad consensus in the Legislative Assembly.

n Unresolved Conflict

The case of the Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge is the chronicle of a complex and unresolved conflict, where three legitimate but often incompatible visions collide: the need to deliver social justice for the historical rights of its inhabitants, the imperative to conserve an ecosystem of incalculable value to the country and the world, and the pressures of economic and tourism development.

Law 9223, created to solve the first issue, ended up aggravating the other two. The 107.9 hectares of forest identified by MINAE are not just a figure; they are the tangible symbol of this imbalance and represent the battleground where the future of the refuge will be decided. Finding a comprehensive and sustainable solution is one of the most urgent challenges for Costa Rica’s environmental and social policy, as the survival of one of its most precious natural treasures depends on it.